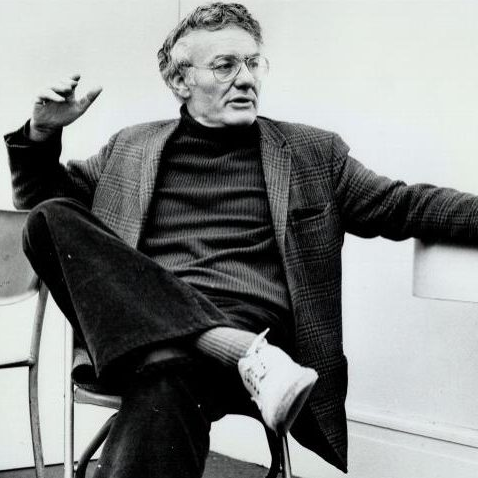

Peter Shaffer in November 1976

Rehearsing a play is making the word flesh. Publishing a play is reversing the process.

Peter Shaffer

Last Thursday Broadway dimmed its lights in memory of British born revered playwright Peter Shaffer. As the darkness descended upon a city that Shaffer had come to love; a moment of quiet reflection was afforded a man who often felt uncomfortable with his status as a cultural icon and giant of the stage.

In the final 23 years of Peter Shaffer’s life, no new pieces of his work were staged and it is perhaps his known discomfort with the final product and his need for constant revision and editing that limited his output in later life. It is this difficulty and struggle that resonates with so many of us who find ourselves frustrated between our vision and our reality. He embodies the perfectionist in all of us that can’t send a text to a loved one without a concentrated proof read; demonstrating that art is not always born as the finished article but refined and reworked like a sculptor chipping away at stone in an effort to uncover the desired image beneath.

“I write many versions of each scene and then tear them up. Or I take a couple of things from the scene and then tear it up. The whole process is a very slow one. Being a playwright is one of the hardest things I think a writer or an artist can be. It’s an endlessly demanding faith; one is never satisfied with anything — ever.”

Peter Shaffer

Shaffer demonstrated that despite the dissatisfaction of the creator; that art can be viewed as great by the many that consume it. Often the essence of what makes something really brilliant is the manner with which people respond to it over time. It can be easy to forget when something becomes such a ubiquitous part of cultural landscape that its creator might find that experience overwhelming but it is something that we can all relate to; the idea of your creation taking on a new or different life. It is the fear that your work won’t stand up to scrutiny; a love-hate relationship with your calling or passion.

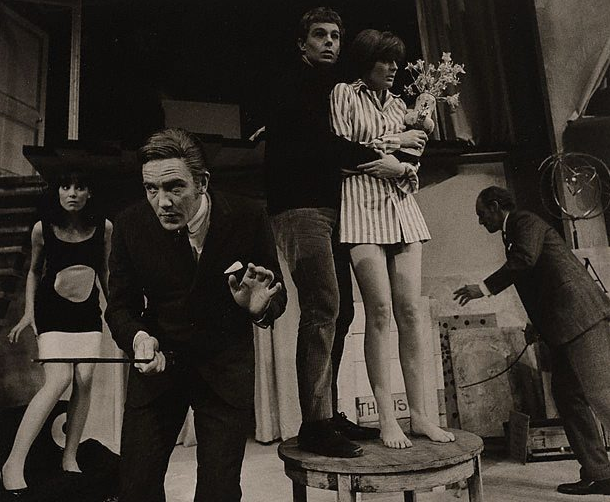

The original 1965 National Theatre Cast of Black Comedy

It is the uncertainty and sense of fear at one’s own worth that resonates with so many of us and helped Shaffer to create some of his most well-known creations. The famous character of Salieri – drawn from history, but very much Shaffer’s own distinct creation –in Amadeus embodying that feeling of frustrated talent; hard work pitted against a natural ease that others so often appear to posses when observed from the outside.

But for so many people across the UK their experience with Shaffer’s work can dig deeper than a voyeuristic experience of the outsider peering in, as the challenge of interpreting great works within amateur groups – who often were drawn to Shaffer due to large cast sizes and recognisable loved titles – is a visceral and personal challenge. Through rehearsal each group finds it’s own perfectionism; each performer strives to revise and improve their performance. In a manner, people become both the characters that Shaffer wrote and some part of the man himself.

Below are two examples from amateur groups who have both recently performed two of Shaffer’s biggest titles; Amadeus and Equus:

The Grange Playhouse players performing Amadeus

I had the privilege of playing Mozart in Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus with a fine cast of amateurs at the Grange Playhouse in Walsall in 2011 as part of their 60th anniversary season. It was my first experience reading Shaffer although I was both familiar with and fond of his screenplay for Milos Forman’s Oscar winning adaptation of the play for the big screen. It sounds almost cliché to say it, but the thing that resonates with me most after working on the play was the layers of depth to Shaffer’s writing. On its surface it’s an excellently crafted narrative of a lifelong professional rivalry. But intricately woven into the dialogue a much deeper argument between Salieri and God emerges and it is here that the real heart and emotional depth of the play resides. Coupled with the childish comedy of Mozart and the strain that is seen in the relationships that develop over the course of the play the writing is a revealing exposition of the human condition. It remains, along with Equus which I have since become familiar with the best of modern British playwriting and I shall treasure the memories I have made in performing Shaffer’s works until I am old enough to tread the boards again as Salieri. –

Adam Worton The Grange Players, Walsall

Putney Arts Centre’s performance of Equus

“Personally speaking it was the most demanding role I’ve ever played – both in terms of subject matter (piecing together the boy’s motives for blinding the horses and Dysart’s own sense of failing) and never being off stage for the whole performance.

I was honoured to have been cast in such a controversial play but knew it was going to be tough going, so much so that I began learning my lines even before I was actually cast (a total of 963 I believe!)”

Michael Rossi, Putney Arts Theatre, Wandsworth

There are countless similar examples of the transformative effects of performing Shaffer’s work; the challenges that face actors as they step into so richly drawn characters with a recognisable dialogue density and the thrill of being able to perform such careful and considered character studies. People take on his plays with an sense of adventure and excited apprehension, and they will continue to take up the challenge just as surely as people will climb mountains or push themselves through marathons.

As the lights dimmed on Broadway last week the end of one act of Shaffer’s work closed with it. But after the curtain falls, it rises once more as lights go up around the country on the incredible body of work that has been left to us all – the most exquisite of gifts. His sense of reinvention and revision will continue to live and grow within the productions that span the globe as everyone involved will seek the same need for perfection, beginning the slow process again – art continuing to grow out of the work left behind.

I think plays, like books, are endemic. They grow out of the soil of the writer and the place he’s writing about. I think, you just can’t move them about, you know.

Peter Shaffer